Pitchmarks #58 - 4th August 2024 - The Piano Cover at the B Conference

(reprinted courtesy of The Links Diary)

Seth Godin tells a story about being backstage, waiting to address a large gathering at an environmental conference. Lacking a theme with which to open his usual free-flowing keynote, he spots a grand piano under a cover, in the corner of the room. On top sits a plaque which reads “Do not place anything on top of this”, and as there is a sign on top of that warning, Seth wanders over to have a look at it, curious about this infringement. And the sign simply says “This is the original Steinway Grand D piano”.

“Not an original; the original, from 1884” explains Seth. The seed of his speech sprouts on the spot, and he reflects that “the folks who built that Steinway in 1884 had no idea that one hundred and forty years later it would be working, it would be creating magic, and we would be talking about it.”

Another story, this time handed down over the years by masters of their craft every bit as valuable as Steinway & Sons, tells of a small party gathered in the dining room of Addington Golf Club, in the summer of 1923. It is decided that a tournament should be held each spring, in order that the alumni of various public schools might do battle on the golf course. As Henry Longhurst recounted, in “My Life and Soft Times”, “the details having been agreed, somebody said, 'now all we need is some bloody fool to present a cup.' At this moment Halford Hewitt walked in, to find himself almost at once to be immortalised as the founder of the best-loved tournament in golf." To steal from Seth, who could imagine that a century later, “The Hewitt” will still be creating magic, and we would still be talking about it?

As Centenaries go, it was magnificent. The customary draw in the East India Club was replaced by a lavish black tie dinner at The Grosvenor, attended by eight hundred and two people, though no one sat still long enough for a headcount of a single table, let alone a ballroom. Friendships were renewed, stories revived, a hundred years of the finest Corinthian spirit washed down with guinea fowl & king oyster mushrooms, and more than a dash of Château la Rivalerie 2015. Or should that be Rivalry…

The speeches were as wonderful as the costumes, and Hewitt traditions such as the corrected pronunciation of certain school’s names by the Secretary of The Public Schools Golfing Society brought a vibrating wave of laughter from the assembled crowd. More than a few statistics were shared, and a great many sepia memories bathed in. But one hundred years on from the first final at Addington, any tribute to the extraordinary legacy of that “bloody fool” Hal could only be condensed, for the drama and the joy emerge in pretty much real time at The Hewitt.

Following the dinner, three months of perpetual rain hampered the practice of even the keenest sides, but as the pavements and hostelries of Deal and Sandwich are suddenly awash with striped socks and blazers, either side of salmon trousers, a vaguely familiar orange glow positions itself above the links, and first-timers are warned that “this never happens at the Hewitt”. But the sun is shining, and the wind picks up, and along the driveway that separates golf’s greatest nineteenth hole from the Deal clubhouse fly 64 flags, depicting the schools present. Or, more accurately, 63, for the clear instruction to provide a 6’ x 2’ flag has been ignored by several team secretaries, and one school’s flag - Blundells - seems to be more like 6 x 2 metres, and is therefore confiscated in the interests of road safety. The Deal Secretary is overheard saying that the offending banner is “large enough for a ship”, and has more or less filled his office. Blundells would not add their moniker to the gold leaf list of winners this year, but perhaps flag-gate will make it into next year’s edition of the infamous Trivia Book.

You’d expect ninety-two Hewitts - a streak only interrupted by warfare and pandemic - to have provided some interesting data, but Sam Smale’s latest edition feeds staggering facts at an alarming rate. More than a dozen players have appeared for fifty years or more, and one individual has featured in seven different decades. Another managed to tot up thirty-six consecutive wins; contrast that with the poor, anonymous soul who lost twenty-seven on the bounce. It is not clear if those two played each other…

Twice a hole has been won in no fewer than eleven strokes, and one match concluded on the twenty-eighth green, after a second pit-stop at the hut. The walk in from there is generally into a sou-wester and fairly arduous; for the losing side, it must have felt like an eternal trudge along that ancient highway, and one wonders if they stopped at the hut a third time en route, to take the edge off that bitterest of defeats. Bernard Darwin once labelled that Hewitt golf which puts up a strong fight only to lose “good useless golf”, and it is hard to imagine a more pertinent example.

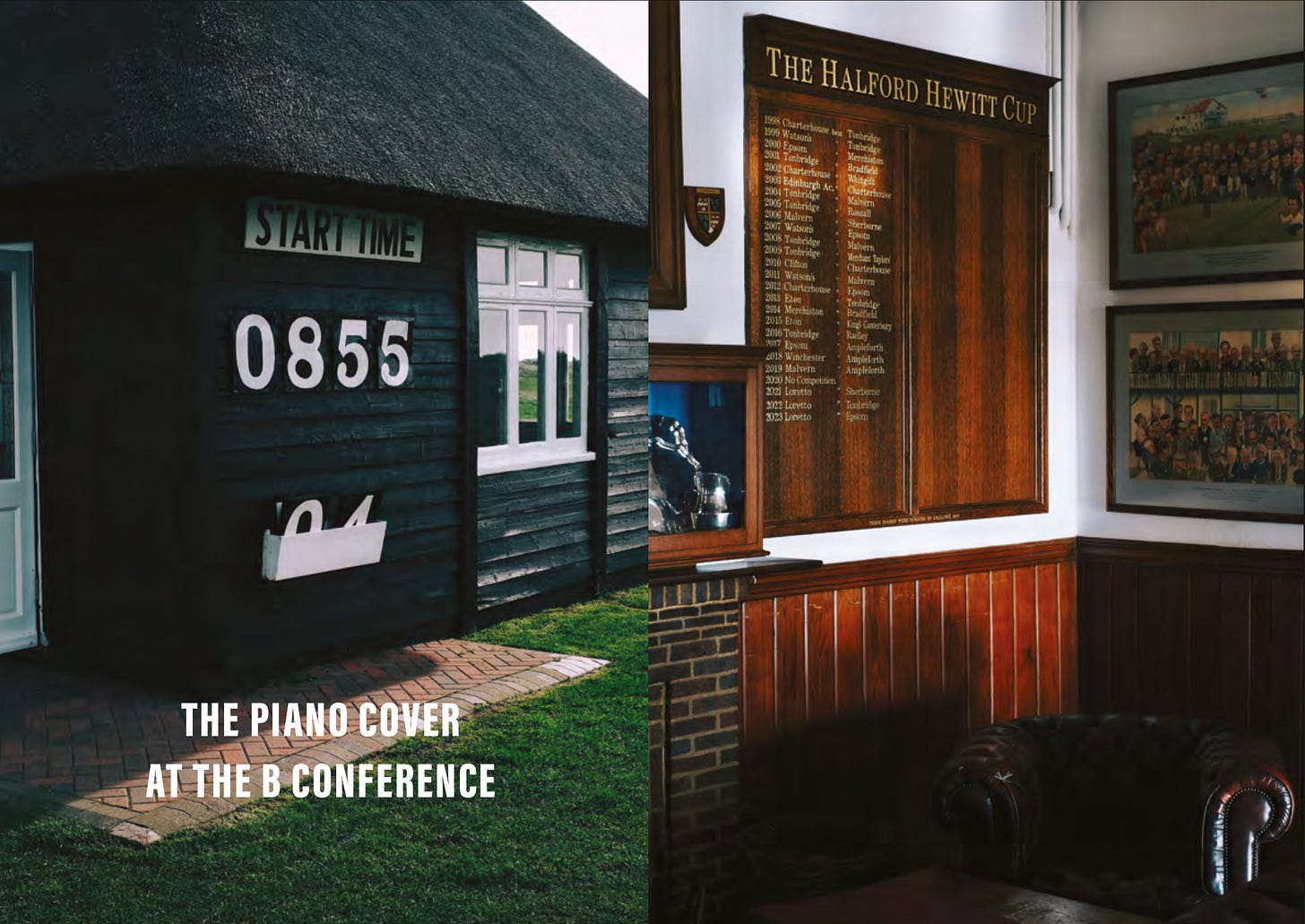

For those of us resident inland over a very long winter, the condition of the golf courses was a joy to behold. From the painted starting time plates at the first to the Bovril-clad hut and beyond, “George’s” was magnificent, the fescue turf firm and bouncy. Deal was in no less fine fettle; the tight run-offs confounding player after player, and around the edges, classic Hewitt touches were in evidence.

The results board in the Deal hallway has seen some action - to quote Seth once more it has “patina on the patina” - but the cards on which each school is required to submit their teams and results are of a size unknown beyond that golf administration office. Stocks are checked in the fall, and occasional calls must be had with paper suppliers, involving repeated, patient explanation of the dimensions, for no recognised measure will fit in the ancient timber slots. Only “Hewitt card” will do.

The results software is equally anachronistic. A small blue window hangs in the top-left corner of a monitor screen and, like the slots in the draw-board, its proportions are static. One strikes “F” to move forward to the next result; “B” to move back, and in between each keystroke lies a delicate silence during which the operative wonders whether this system will die now or later. Yet it persists, like the Hewitt card, like that model D piano. Somehow this reluctance to change or alter something that is very much unbroken is refreshing, and precious.

Now and then, you might spot a player hiding in a corner on a call, trying to find a room for the night after an unexpectedly good result. But for every such winner, another player is driving home, the dream on hold for another year. The Deal balcony is busy throughout, though when a match is spotted coming down the last, the crowd swells in anticipation of further drama. Darwin, a regular for Eton in their dominant early years, also wrote that “it is impossible to imagine more delicious heights of joy, more profound depths of depression, more agonising moments of suspense than are suffered by the supporters…when the last foursome comes to the last green and everything hangs on the last putt”, and the tournament records show that he spent time on both sides of this tightrope as a player as well. Now and then, a match will not shake hands on the last, and two of their number will be seen traipsing back to the first tee. By that point, the fairway must seem like a ribbon and the whole routine some wretched deja vu but it seems wrong to look away from this lottery, and so no-one does.

Some devices are used to try and predict the scores - the printed Anderson Scales and Smale Scales are clasped in many hands, though not everyone pretends to understand them. There are odds, of course, but this is golf, and spread over a century and twenty-six thousand games, most things that can happen, have happened. But this year is different in that, while most of the schools claim that they don’t mind who wins “as long as it isn’t Eton”, mutterings have been made about the rather keen approach of Loretto, who arrive in town looking for a fourth straight win, after an aggressive recruitment policy.

Only one side has managed that feat - Charterhouse - who somehow won seven of the ten Hewitts before the war, including that unique streak of four. But it isn’t to be for Loretto, as Uppingham dismantle Blundells at Sandwich, packing them home via a visit to the Deal office to collect their ship’s flag, before inflicting a similar beating on the holders. Eventually, Tonbridge see off Uppingham, and Eton see off Tonbridge, and those hardy souls remaining on the coast by Sunday afternoon dream of a surprise, for Bedford are somehow in the final after only one semi-final in their eighty-five previous attempts.

But a hundred years after Darwin featured in the inaugural final against Winchester - winning his match 9&8 in a furious attempt to spare those present the “agonising moments of suspense” - his beloved alma mater would prevail, the thirteenth time Eton had hoisted old Hal’s famous trophy.

And so I reluctantly pack up my stuff, and head back to the van and then up through the Wealds of Kent and home, and Seth is once more with me for company, and I listen to him say again, though it hits me a different way post-Hewitt “there’s no guarantee that what we do is going to be around in 140 years, but we could act like it might be, we could say this thing we’re doing together is…important. And there are lots of kinds of important - it could be important to one person, it could be important a century from now. But this idea that the piano is still here? It gave me chills”.

I’ll never play Hewitt golf; ineligible on both choice of school and golfing grades. And I might never play a Steinway model D, either. But the fact that both things are still around - each the result of a spark of creative inspiration a very long time ago - seems to me more important by the day.

I watched a Hewitt. It gave me chills.

What a history, well told!

Yet another great piece from Richard's mighty pen. I've never been to the Halford-Hewitt nor every likely to go but at least now I understand the romance.