From its inception, Woking has held a privileged spot in the history of English golf. Opened in 1893, it was the first of the Surrey and Berkshire heathlands in an area that now boasts many of the world’s finest inland courses.

An early review from Bernard Darwin, who joined in 1897, outlines how popular the club was. “The waiting list at Woking is so long,” he wrote, “that when at last the Committee proposed to elect a candidate he was generally found to be dead.” The original members were mostly London-based, travelling out to Surrey on the same train line that had for a while brought corpses out of the metropolis, until cremation became legal and the vast cemetery at Brookwood - owned by the London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company - became available for other purposes, such as golf.

In the first couple of decades of the twentieth century, two local members would transform the reputation of Tom Dunn’s course through a series of improvements. John Low and Stuart Paton were amateurs in a time when course design was emerging as a profession, rather than a sideline for club professionals, and it is hard to overstate their influence on what became known, in the Golden Age of golf architecture, as the strategic school of design. One by one, Low and Paton set about removing penal cross-bunkers and replacing them with carefully sited, individual hazards, as well as creating internal green contours that perplex golfers to this day.

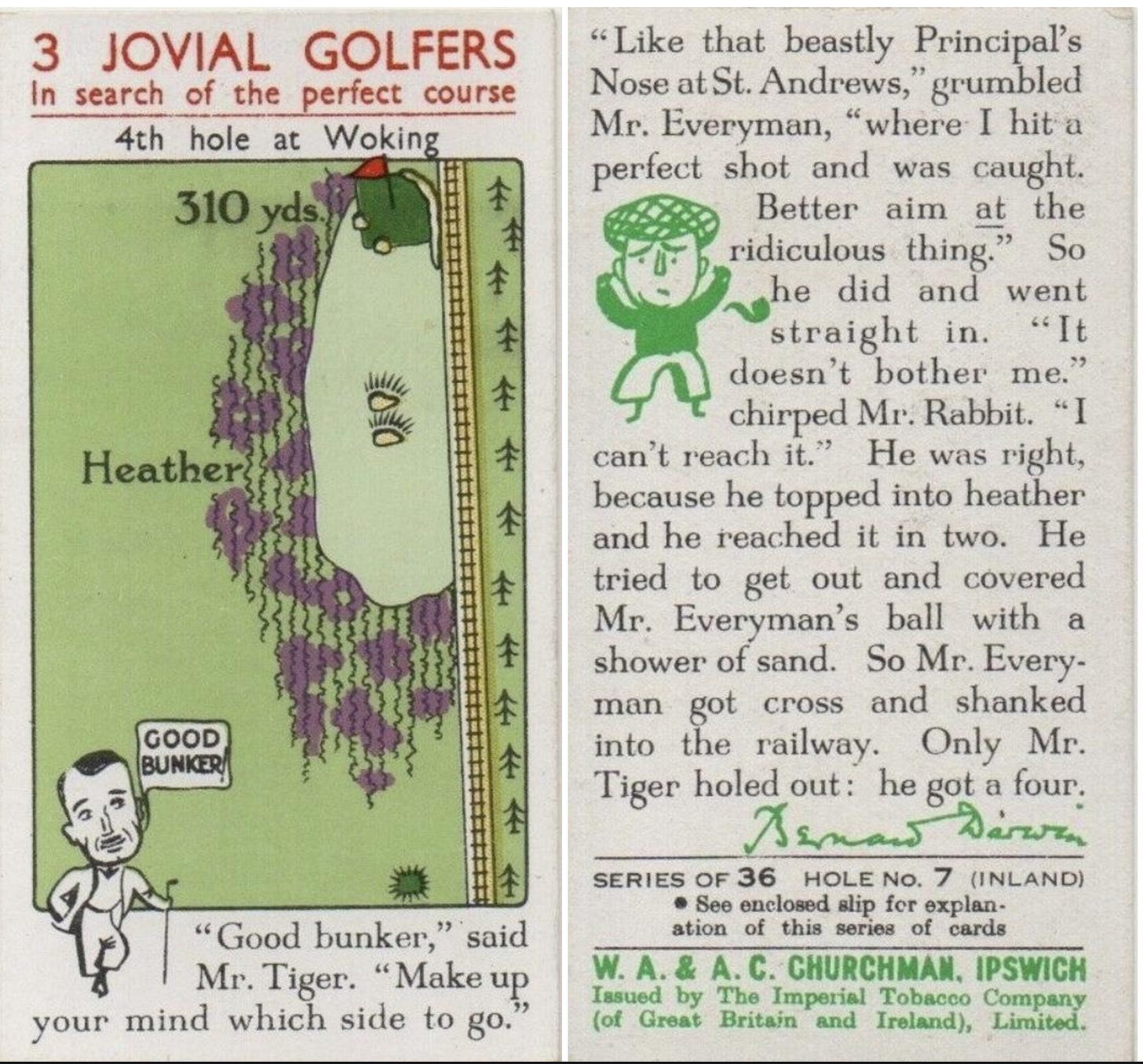

A forced carry approach to the penultimate hole was swapped for one single trap built into the right-hand side of the green - the “Johnny Low bunker” - and others followed at the 3rd and 11th. But one development caught the attention like few other moments in golf architecture’s timeline. In the centre of the 4th fairway, they positioned a tribute to the “Principal’s Nose” bunker complex at St Andrews. Unlike the original, these nostrils - on the exact line one would choose to avoid the railway running down the right side of the hole - were man-made and thus the subject of a great deal of controversy within the membership. The effect of this single hazard on a young Tom Simpson is well documented, for it changed his life. Not long after his first encounter with the new 4th , he resigned from a London law firm and began another journey - as a golf course architect.

Woking’s place as a wellspring of thoughtful design was secured, but for the first four decades of golf across the heath, the enduring puzzle of how best to climb from the wonderful 8th to the plateau through which the back nine weaves went unmentioned in the press and the board minutes. From the 8th tee, the original layout featured a run of six consecutive par-fours, followed by back-to-back par-fives, so perhaps there was a sense that more variety might help the flow of the course around this central stretch, but the archives offer nothing until the late 1930’s.

At a Committee Meeting in March of 1937, those present (including Paton, who by now was known as “The Mussolini of Woking,” thanks to his good friend Darwin) approved the election of three Honorary Members, the last of which was Tom Simpson, for whom this was granted “in recognition of the valuable help he gave in connection with the reconstruction of the 13th hole.” Notes accompanying the 1928 Accounts mention “the great loss which the Club has sustained by the death of Mr. John L. Low…[which] left a gap which cannot be filled,” but it is clear that Simpson stepped into the breach to assist in Paton’s tireless evolution of the Woking course.

Jim Connelly’s book, A Temple of Golf, notes that Simpson and Paton worked together on various holes, including diverting the stream on the 6th to create the diagonal hazard that exists today. But it was the redesign of the 9th and 10th holes that caught the attention of the golfing public. In an early review, Charles Ambrose described the difficulties of the original 9th, which required a walk back from the 8th green for a semi-blind drive across a quarry, followed by a blind second. In another piece the following week, he singles out the 10th as “the weak spot at Woking.”

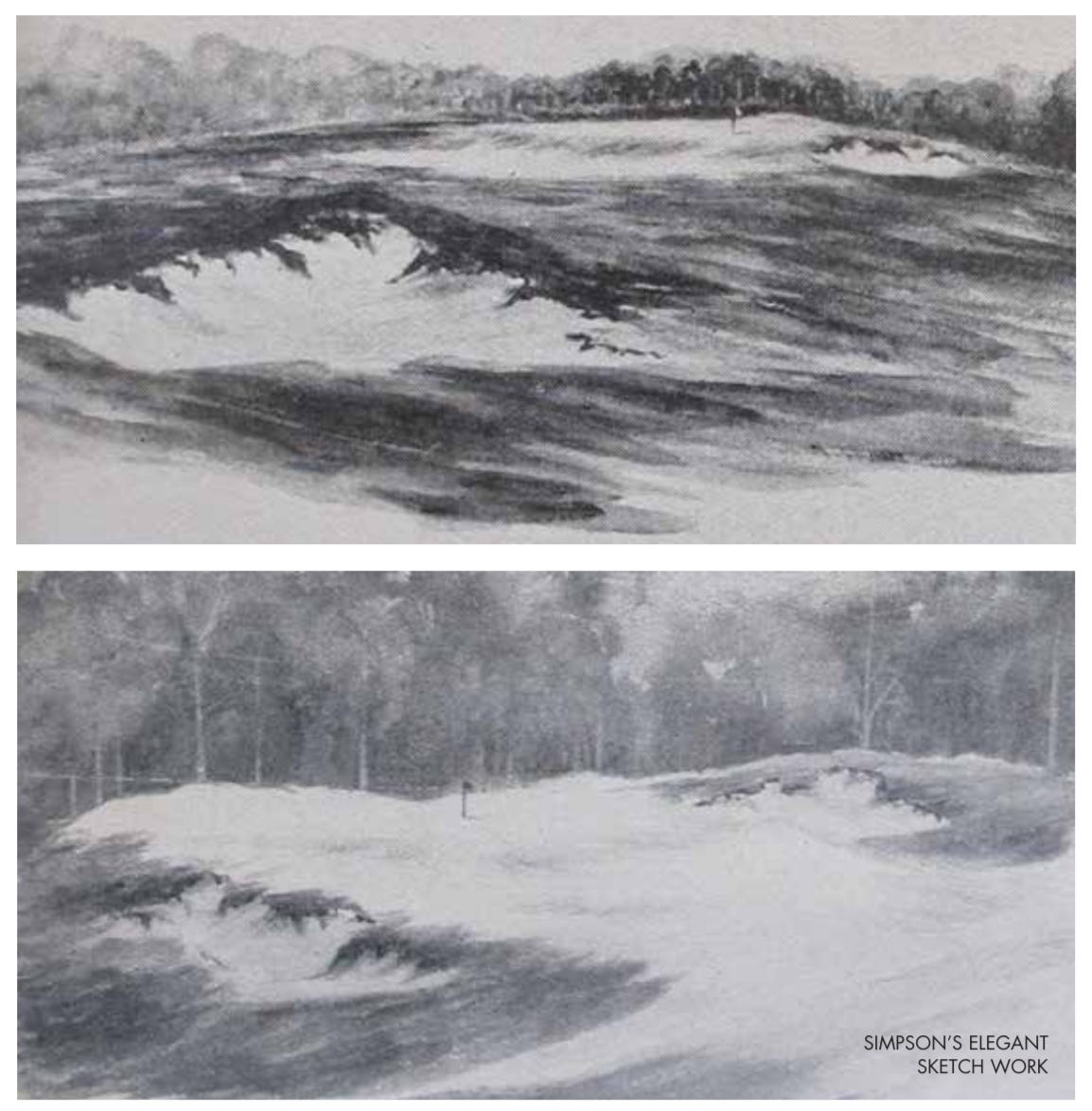

The Simpson-Paton solution was to create a new 9th tee behind the 8th green, thereby removing the irritation of backtracking, and to bring the 9th green towards the tee, using the ridge that previously obscured the approach as a feature in a contoured green guarded by a right-hand bunker. From there, one walked left to play a 10th that no longer climbed straight up the hill but worked across the slope to a green whose remnants accept today’s short irons—albeit from an angle that feels incongruous.

Ambrose judged the new 9th as “excellent, both in conception and execution,” and the following week, in Golf Illustrated, he described the 10th as “the most daring piece of work I have yet seen from Tom Simpson,” going on to suggest that, with two central hazards as his own version of the paradigm-shifting “Nose” six holes earlier, “this hole may easily become one of the grandest in all of golf.” Thirty-five years from the moment Simpson’s career trajectory changed—when he realised “the importance of golf architecture as an art as well as a science”—he found the opportunity to solve this question of altitude and pay tribute to the St Andrews links which both he and Low so revered.

At one point, Ambrose claimed that “nobody—not the most inveterate of ‘die-hards’—could mourn the passing of such a feeble hole.” Not even Bernard Darwin, whose love of adventurous golf meant he would “shed one sentimental tear over the old ninth,” could say anything of value about the old 10th. He began a Times piece called “Change but not decay” with, “I said to a friend the other day that I was going to look at the two new holes at Woking. He replied: ‘that sounds like blasphemy.’” But Darwin then offered his view of this latest change: “[F]ar from being a sudden and impious outrage, [it] is part of an orderly process of evolution.”

Later he imagined the player taking on the risks of the new 9th, and upon success, “striking the stars with uplifted head.” Of the 10th, he reported that, “there are already some to abuse it vehemently and others to call it a ‘great hole.’” So the controversy that surrounded the 4th hole bunker from 1902 onwards had come full circle for Simpson. In this course-correction, perhaps he had created his own “mad masterpiece,” as he termed those holes that approach the edge of reason.

On the Saturdays either side of that piece, Darwin reported on the visits of the Oxbridge blues sides, against which a certain J.S.F. Morrison would represent Woking. Though the new holes were being played, Darwin deemed this “too tremendous a subject to deal with briefly. When Mr Paton and Mr Simpson conspire darkly together the result deserves an article itself.” When it landed, Darwin’s enthusiasm for the dark conspiracy spoke volumes. Morrison (who was at this point a decade into partnership with Colt & Alison) claimed 3.5 points from a possible 4 in the two Varsity warm-ups, though the match reports don’t reveal what he made of the new holes.